Ghost at the Table-- Reminiscences of My Budo Study...

I’ve started, albeit a bit late to collect a “new” old compendium of my recollections and experiences in the noble pursuit of promoting good budo 武道at the Rembukan.

My ramblings probably won’t follow any particular order of importance, sequence or chronology. It’s a good bet that I will inadvertently jump from subject to subject acquiescing to whim and self-indulgence. I’ll sprinkle in redundancies and discrepancies from earlier writings for good measure and bait any grammarians amongst you, to pick up the sword in anger. You might be tested by my prodigious bafflegab (yes this is a real word that I’ve fallen in love with -it’s autobiographical).

Now that you’ve been warned, I’d like to explain how this essay came about.

Creating a Dojo 道場

You’ve graced my round table like knights of the realm or more like knights out of a Monty Python movie. Seriously though, the table has served like a sentinel standing witness to momentous occasions, accidental epiphanies, long translations, and deafening silences in the company of family, Menkyo Kaiden, various guest instructors, students, and friends alike. Oh, let’s not forget the food and drink!

I didn’t know when I opened my home to my dojo mates, the remarkable as well as the unremarkable, regardless of their tenure, that all would leave some wisp of themselves behind, memories penned in indelible ink.

Forming a dojo wasn’t as straightforward as I had naively thought at the time. My thinking was that I needed a place to practice the arts that I loved. My second thought was to find someone to practice with. At some point I harbored thoughts about having something that would encourage my teachers to visit the Rembukan.

Some of them had professed that they didn’t want to travel outside of Japan and to the U.S. in particular. (Maybe I’ll write about this later.)

I was not prepared and wholly unarmed to appreciate that a dojo is organic, a living thing and not a “place”. It seems obvious now. I couldn’t anticipate that for some of you, our only common denominator being the dojo, that you would become more like family than students. Perhaps not in equal measure, you have brought us joy and disappointment.

Thus, sitting at my table, conjures up reminiscences about a rich and textured past. There’s a story here. These recollections sometimes trigger new insights too, something worth re-examination and possible transmission. My dining table became the scene of the crime serving as both anchor and portal, an accidental adjunct to the dojo mat.

With vivid clarity and detail, often nuanced, these spectral thoughts are sometimes intrusive and untimely. Re-examination of the past often adds a depth of understanding to my truths. And now I want to share them knowing and risking that today’s “truth” might be tomorrow’s “fiction” in need of revision.

I’m reminded of something attributed to an early Roman Emperor that I was wholly unprepared for when I launched a dojo and invited students into my home and the presence of my family. “Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. And everything we see is a perspective, not a truth”.

By definition, thoughts are transient and dynamic things. What is conjured up at the table vanishes in a breath, if I fail to seize the opportunity. This might be attributed to advancing age. I have a starring role in each of these memories. The plot sometimes begs an accounting and a reconciliation of our ledger of Rembukan history.

Pursued by the demons of shoulda, coulda, woulda, I contemplate the “what ifs’”, going thru the gymnastics of different scenarios in the pursuit of altered outcomes judged retrospectively as credits and debits. With this new accounting, I have no idea what the final balance sheet will or even should look like! Indeed, I wonder if this exercise stimulates mental agility or looming senility.

This isn’t a negative thing. I’m not dwelling in a miasma of guilt-driven, perverse cathartic rhythms given to a troubled soul. To the contrary, I’ve invited the ghosts to my table.

I take sanctuary in knowing that I’ve always tried to maintain my personal integrity and do the right thing. I understood the consequences of decisions that would affect those that I love and those for whom I have some responsibility.

Correctly or with wholesale delusional abandon, I’ve tried to keep my moral compass pointing north with the goal of being consistent not intractable. For some, I suspect that this would not be their description of my public demeanor. Still, I’ve earnestly tried to be elastic enough to keep doors open to compromise as long as doing so did not threaten what we are trying to accomplish and the spirit of the Rembukan. My propensity for excess aside, I’m aware that my actions have sometimes been predicated upon flawed and imperfect information.

There is an obligation to set things right when a wrong has been uncovered.

I believe that anyone that has ever been compelled to teach, implicitly understands the blessings and curses of the many decisions that add up over years.

Finally, it can be argued that these musings might be better platformed and organized but I’ll leave this open checkbook for you to reconcile. Consider this a form of your “shyugyo”. (修行)

As I was drafting this, auspiciously, Yuri asked me a question at breakfast. It was an odd question based upon a notion that a certain behavior was singularly a Japanese trait.

She used the term “Natukashi” 懐かしい (natukashimu is the verb) and asked if we had such a word in Western culture? (I love it when she assigns me the task of grand arbiter first thing in the morning – and as you know, I don’t even drink coffee!).

We went on to discuss her readings of a modern monk who researched the word dating back to the oldest writings in Japan with the “Manyoshyo” 万葉集. The concept could not be found in original Chinese from which written Japanese was born. It was wrongfully concluded, in my opinion, that since there was no word descriptor, in Chinese, that there would be no equivalent feeling associated with it either. This gave “Natukashi” 夏樫 great power. The concept was deemed unique and therefore cherished to the extent of being elevated to a Japanese virtue.

How interesting and how coincidental to my writings that once understood, “natukashimu” 懐かしむ means to reminisce with one caveat. In Japan, the context is always positive whereas we can use the word “reminisce” to connote negative associations as well. How affirming it is to me, that to Japanese sensibilities, my writings are a “virtue”.

My ramblings probably won’t follow any particular order of importance, sequence or chronology. It’s a good bet that I will inadvertently jump from subject to subject acquiescing to whim and self-indulgence. I’ll sprinkle in redundancies and discrepancies from earlier writings for good measure and bait any grammarians amongst you, to pick up the sword in anger. You might be tested by my prodigious bafflegab (yes this is a real word that I’ve fallen in love with -it’s autobiographical).

Now that you’ve been warned, I’d like to explain how this essay came about.

Creating a Dojo 道場

You’ve graced my round table like knights of the realm or more like knights out of a Monty Python movie. Seriously though, the table has served like a sentinel standing witness to momentous occasions, accidental epiphanies, long translations, and deafening silences in the company of family, Menkyo Kaiden, various guest instructors, students, and friends alike. Oh, let’s not forget the food and drink!

I didn’t know when I opened my home to my dojo mates, the remarkable as well as the unremarkable, regardless of their tenure, that all would leave some wisp of themselves behind, memories penned in indelible ink.

Forming a dojo wasn’t as straightforward as I had naively thought at the time. My thinking was that I needed a place to practice the arts that I loved. My second thought was to find someone to practice with. At some point I harbored thoughts about having something that would encourage my teachers to visit the Rembukan.

Some of them had professed that they didn’t want to travel outside of Japan and to the U.S. in particular. (Maybe I’ll write about this later.)

I was not prepared and wholly unarmed to appreciate that a dojo is organic, a living thing and not a “place”. It seems obvious now. I couldn’t anticipate that for some of you, our only common denominator being the dojo, that you would become more like family than students. Perhaps not in equal measure, you have brought us joy and disappointment.

Thus, sitting at my table, conjures up reminiscences about a rich and textured past. There’s a story here. These recollections sometimes trigger new insights too, something worth re-examination and possible transmission. My dining table became the scene of the crime serving as both anchor and portal, an accidental adjunct to the dojo mat.

With vivid clarity and detail, often nuanced, these spectral thoughts are sometimes intrusive and untimely. Re-examination of the past often adds a depth of understanding to my truths. And now I want to share them knowing and risking that today’s “truth” might be tomorrow’s “fiction” in need of revision.

I’m reminded of something attributed to an early Roman Emperor that I was wholly unprepared for when I launched a dojo and invited students into my home and the presence of my family. “Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. And everything we see is a perspective, not a truth”.

By definition, thoughts are transient and dynamic things. What is conjured up at the table vanishes in a breath, if I fail to seize the opportunity. This might be attributed to advancing age. I have a starring role in each of these memories. The plot sometimes begs an accounting and a reconciliation of our ledger of Rembukan history.

Pursued by the demons of shoulda, coulda, woulda, I contemplate the “what ifs’”, going thru the gymnastics of different scenarios in the pursuit of altered outcomes judged retrospectively as credits and debits. With this new accounting, I have no idea what the final balance sheet will or even should look like! Indeed, I wonder if this exercise stimulates mental agility or looming senility.

This isn’t a negative thing. I’m not dwelling in a miasma of guilt-driven, perverse cathartic rhythms given to a troubled soul. To the contrary, I’ve invited the ghosts to my table.

I take sanctuary in knowing that I’ve always tried to maintain my personal integrity and do the right thing. I understood the consequences of decisions that would affect those that I love and those for whom I have some responsibility.

Correctly or with wholesale delusional abandon, I’ve tried to keep my moral compass pointing north with the goal of being consistent not intractable. For some, I suspect that this would not be their description of my public demeanor. Still, I’ve earnestly tried to be elastic enough to keep doors open to compromise as long as doing so did not threaten what we are trying to accomplish and the spirit of the Rembukan. My propensity for excess aside, I’m aware that my actions have sometimes been predicated upon flawed and imperfect information.

There is an obligation to set things right when a wrong has been uncovered.

I believe that anyone that has ever been compelled to teach, implicitly understands the blessings and curses of the many decisions that add up over years.

Finally, it can be argued that these musings might be better platformed and organized but I’ll leave this open checkbook for you to reconcile. Consider this a form of your “shyugyo”. (修行)

As I was drafting this, auspiciously, Yuri asked me a question at breakfast. It was an odd question based upon a notion that a certain behavior was singularly a Japanese trait.

She used the term “Natukashi” 懐かしい (natukashimu is the verb) and asked if we had such a word in Western culture? (I love it when she assigns me the task of grand arbiter first thing in the morning – and as you know, I don’t even drink coffee!).

We went on to discuss her readings of a modern monk who researched the word dating back to the oldest writings in Japan with the “Manyoshyo” 万葉集. The concept could not be found in original Chinese from which written Japanese was born. It was wrongfully concluded, in my opinion, that since there was no word descriptor, in Chinese, that there would be no equivalent feeling associated with it either. This gave “Natukashi” 夏樫 great power. The concept was deemed unique and therefore cherished to the extent of being elevated to a Japanese virtue.

How interesting and how coincidental to my writings that once understood, “natukashimu” 懐かしむ means to reminisce with one caveat. In Japan, the context is always positive whereas we can use the word “reminisce” to connote negative associations as well. How affirming it is to me, that to Japanese sensibilities, my writings are a “virtue”.

Dreaming… 夢

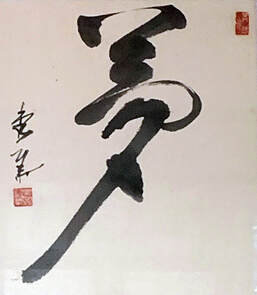

In the dojo, there are several brush writings by Kuroda, Ichitaro Sensei. He was famous for many things including his budo and his shodo (brush-writing) 書道 skills.

I’d like to talk about one brush writing in particular. You see it in the dojo. It is the ideogram, “Yume” which translates as “dream”.

As to how I came into possession of this gift I have a story to tell. I was living in Japan, and Kaminoda Sensei was going for his Hachidan in Iaido at the Butokuden 武徳殿in Kyoto. I was invited to witness it. Back then, you didn’t see many non-Japanese at this kind of event, or even at this venue. In my recollections, only my sempai Bruce and I were present. It was the Golden Week holiday, when by custom EVERYONE travels. Everything was booked solid and every train was packed like sardines.

After witnessing the successful test, we were returning to Tokyo. Kuroda Sensei and I shared the aisle together as there were no seats. As he was older and a Sensei, I offered to hold his bag. He refused but I eventually wore him down. I knew better than to ask for his weapons bag! In the course of travel, he presented me with one of his coveted writings. It was something that made me very happy. It was arguably, the most valuable thing I possessed in Japan other than my iaito. Ah, the good ole days, to be free of the weight of physical encumbrances… I didn’t appreciate just how significant my brush writing was at the time as Sensei was a prolific writer to say the least.

But the story and the brush-writing have continuously enriched our lives over the years. It was the first gift of value that I could share with Yuri, when we were courting. Erh, maybe down the road I’ll tell you a scary story about getting the proper frame but not now and not sober!

Until recently, we accepted as most Japanese would, the obvious meaning of “Yume”. But Kuroda Sensei knew there was something more to the story and for me to uncover.

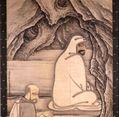

For those of us that have enjoyed reading “Musashi” 宮本武蔵 by Yoshikawa, Eiji, 吉川英治 Zen monk by the name of Takuan is introduced as a mentor that taught the philosophical aspects of kenjutsu to Musashi. The writer took license as this was pure fiction.

Takuan 沢庵 existed, though today, for some, his reputation is pinned to a radish pickle named after him. Takuan was known for authoring “Kenzen” 剣禅一味. He influenced Yagyu Ryu Kenjutsu, then popular and adopted by the Tokugawa Shogunate in Edo. This Ryu-ha later became the basis for Kendo.

Upon his deathbed, Takuan ’s collected deshi begged one last request. Would the master please write one more brush writing? He chose “yume” and it took all of his remaining effort.

Today, we might be forgiven a superficial understanding of the concept. But for Takuan, as death loomed, he reached satori where all one’s past efforts looked like a continuous and shallow dream, flowing like a stream, light, not weighty, transcendental, not worldly, a lesson within a lesson to be absorbed. For me, perhaps this is the “ura” to my “omote” of “Do” or “michi”. I regret, that at the time I was unaware of the full message that Kuroda Sensei was trying to impart.

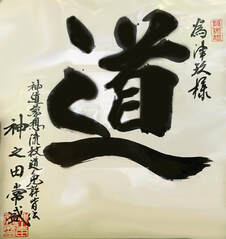

“Do / Michi” 道

Sometimes, life with Yuri seems like a game show. I’m confronted with questions, posed as a pass/fail test. Her inquiries (always a trap) typically signal trepidation on my part. With this episode I was asked: When looking at your “michi” is your road made after you (looking forward into the future) or before you (looking to your past)? My collective experiences are my “DO/Michi”. Fortunately, some famous modern Zen Priest and author corroborated my view and I survived another challenge.

Isn’t it, so “Japanese-budo-like” to have a contradiction exist in something seemingly so basic and simple to understand!

Early on, Kaminoda Sensei, who also did shodo as he learned it from Kuroda Sensei, invented a meaning for the kanji for “do/michi” for me. If you look (kanji are kind of like a Rorschach test or like a drunk chicken ran thru a puddle of ink.) it looks as if there is a road traveling from right to left going slightly uphill. At an intersection, the road splits and goes almost vertical. Then out of reach is another mark. To the right, is a picture of a man, the shoulders and head are separated by a slash (as in sword cut). Sensei said that the road isn’t easy. It is common to lose track and go off the trail. At the top of the mountain and the end of the trail, just out of reach is the goal – the other mark. If you’ve chosen a worthy goal to travel in life, you should be willing to sacrifice yourself in pursuing its’ end. Yuri’s fairly certain that he made this up and that I must’ve been the only one that he told but I’m absolutely certain that I didn’t make it up!

Isn’t it, so “Japanese-budo-like” to have a contradiction exist in something seemingly so basic and simple to understand!

Early on, Kaminoda Sensei, who also did shodo as he learned it from Kuroda Sensei, invented a meaning for the kanji for “do/michi” for me. If you look (kanji are kind of like a Rorschach test or like a drunk chicken ran thru a puddle of ink.) it looks as if there is a road traveling from right to left going slightly uphill. At an intersection, the road splits and goes almost vertical. Then out of reach is another mark. To the right, is a picture of a man, the shoulders and head are separated by a slash (as in sword cut). Sensei said that the road isn’t easy. It is common to lose track and go off the trail. At the top of the mountain and the end of the trail, just out of reach is the goal – the other mark. If you’ve chosen a worthy goal to travel in life, you should be willing to sacrifice yourself in pursuing its’ end. Yuri’s fairly certain that he made this up and that I must’ve been the only one that he told but I’m absolutely certain that I didn’t make it up!

“Kamae” 構え

Recently, Yuri and I were at the table talking about “kamae”. We use the term to express that ready posture that begins training and is emphasized within each kata. The concept is so much more.

It concerns me that many of these concepts lose something with writing, as if writing is the form and it bends the meaning to its convenience. The meaning is at risk of being more limiting and narrower in scope when the broadest understanding is a truer thing.

I was thinking of an American construct of a Japanese word. This alone is enough to get me into trouble. I hear “mae” 前or front as part of “ka – “mae”. But kamae is actually only one character not two. It’s a picture of a structure such as a building. Architects use the term differently, “kochiku” 構築 or “ko (kamae) 構 and “chiku” 築 (to build) thus demonstrating how pliable and pervasive this concept is within Japanese society.

Delightfully, Yuri and I hustled off track and I learned something new about my bride of 40 years that startled me! If you were to say, “table” for example, whether in English or Japanese, her first mental image is of the kanji, the ideogram used to express table. What? Huh? Really? I don’t believe it!

If you say the word table to me – I don’t picture t-a-b-l-e! I picture some form of a table, an image of the thing the letters portray.

I’m not sure how this impacts our thought processes, let alone communication but I’m certain its’ mind-boggling. Yuri doesn’t seem to find it as much so.

Spiraling out of control with this, I didn’t know that all Japanese children, when starting school were taught, almost as a compulsory mantra the concept of “kokorogamae” 心構え. Kokoro 心 means heart and gamae構えis still kamae構え (don’t ask) which I’ll translate as steeling one’s heart to prepare for school and life. It’s a concept so ingrained that it is taken for granted.

In Jodo, we use “Kigamae” 気構え.

Kaminoda Sensei and Yuri had a special bond. He often told her that she had “kigurai” 気位 which I will convey to you as “initial meeting stance”. We might liken it to the saying attributed to Will Rogers, as “you never get a second chance to make a first impression”. How you meet and interact, shows your stance towards others. This concept is NOT limited to budo. It permeates life. Proper and sincere execution demonstrates dignity and gravitas. When going “thru the motions”, it is theatre and not particularly good theater.

Yuri and I continued to meander. She was surprised that I was aware that actors in Noh, 能 do not start at the edge of the curtain to come on stage. I knew that these actors started to prepare to the musical cues and floor vibrations deeper backstage and long before coming into view. I didn’t know that the runway could be 30 feet long! This allows the Noh master, to fully transition into the part, synching emotions, physicality and breathing into one subtle and powerful whole. Noh training is every bit as austere as old time budo!

I wanted to talk about kamae a little bit in terms of budo.

It is one of those words bandied about and given little thought on the mat and regardless of martial discipline. Maybe this is because the Japanese are already inculcated but there is still a transition to make.

I believe that there is beginner’s kamae. It grows in power with increased skill sets incrementally. A beginner might only be able to demonstrate weakness and opening whereas someone who really understands, seems to exert power, even in the seeming inaction of kamae.

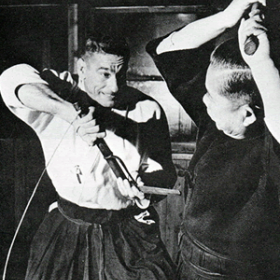

It isn’t about standing, posing and glaring at an opponent. It’s about truly being ready to respond to an enemy bent on causing your destruction. It requires a relaxed readiness as well as a tension to explode into action. In essence, the power you exert controls your adversary and hijacks his movements to conform to your will.

Japanese students are sensitized to this concept from a very early age for a home court advantage. Ergo (I’ve always wanted to work that into a sentence), the teacher doesn’t do much to help guide us. This might be better chalked up to the sin of omission than a desire to conceal the knowledge from a Western student. There is kamae, bowing into the dojo. There is kamae, bowing onto the mat. This in turn, is the thing you do with the first breath to start training, not just kata, but in picking up a weapon and training. Kamae is a state of mind demonstrated with the body. We talk about the “glue” that holds movements together. If that is the case, maybe “kamae” is the gristle.

It concerns me that many of these concepts lose something with writing, as if writing is the form and it bends the meaning to its convenience. The meaning is at risk of being more limiting and narrower in scope when the broadest understanding is a truer thing.

I was thinking of an American construct of a Japanese word. This alone is enough to get me into trouble. I hear “mae” 前or front as part of “ka – “mae”. But kamae is actually only one character not two. It’s a picture of a structure such as a building. Architects use the term differently, “kochiku” 構築 or “ko (kamae) 構 and “chiku” 築 (to build) thus demonstrating how pliable and pervasive this concept is within Japanese society.

Delightfully, Yuri and I hustled off track and I learned something new about my bride of 40 years that startled me! If you were to say, “table” for example, whether in English or Japanese, her first mental image is of the kanji, the ideogram used to express table. What? Huh? Really? I don’t believe it!

If you say the word table to me – I don’t picture t-a-b-l-e! I picture some form of a table, an image of the thing the letters portray.

I’m not sure how this impacts our thought processes, let alone communication but I’m certain its’ mind-boggling. Yuri doesn’t seem to find it as much so.

Spiraling out of control with this, I didn’t know that all Japanese children, when starting school were taught, almost as a compulsory mantra the concept of “kokorogamae” 心構え. Kokoro 心 means heart and gamae構えis still kamae構え (don’t ask) which I’ll translate as steeling one’s heart to prepare for school and life. It’s a concept so ingrained that it is taken for granted.

In Jodo, we use “Kigamae” 気構え.

Kaminoda Sensei and Yuri had a special bond. He often told her that she had “kigurai” 気位 which I will convey to you as “initial meeting stance”. We might liken it to the saying attributed to Will Rogers, as “you never get a second chance to make a first impression”. How you meet and interact, shows your stance towards others. This concept is NOT limited to budo. It permeates life. Proper and sincere execution demonstrates dignity and gravitas. When going “thru the motions”, it is theatre and not particularly good theater.

Yuri and I continued to meander. She was surprised that I was aware that actors in Noh, 能 do not start at the edge of the curtain to come on stage. I knew that these actors started to prepare to the musical cues and floor vibrations deeper backstage and long before coming into view. I didn’t know that the runway could be 30 feet long! This allows the Noh master, to fully transition into the part, synching emotions, physicality and breathing into one subtle and powerful whole. Noh training is every bit as austere as old time budo!

I wanted to talk about kamae a little bit in terms of budo.

It is one of those words bandied about and given little thought on the mat and regardless of martial discipline. Maybe this is because the Japanese are already inculcated but there is still a transition to make.

I believe that there is beginner’s kamae. It grows in power with increased skill sets incrementally. A beginner might only be able to demonstrate weakness and opening whereas someone who really understands, seems to exert power, even in the seeming inaction of kamae.

It isn’t about standing, posing and glaring at an opponent. It’s about truly being ready to respond to an enemy bent on causing your destruction. It requires a relaxed readiness as well as a tension to explode into action. In essence, the power you exert controls your adversary and hijacks his movements to conform to your will.

Japanese students are sensitized to this concept from a very early age for a home court advantage. Ergo (I’ve always wanted to work that into a sentence), the teacher doesn’t do much to help guide us. This might be better chalked up to the sin of omission than a desire to conceal the knowledge from a Western student. There is kamae, bowing into the dojo. There is kamae, bowing onto the mat. This in turn, is the thing you do with the first breath to start training, not just kata, but in picking up a weapon and training. Kamae is a state of mind demonstrated with the body. We talk about the “glue” that holds movements together. If that is the case, maybe “kamae” is the gristle.

About the perspective of learning…

An ancient Chinese sage in the 4th century BCE is attributed with a pithy saying that I really like: “Knowing doesn’t win over liking, which doesn’t win over enjoying”.

How often have I seen this played out over the years? We’ve all witnessed the impassioned dojo mate with endless exuberance blathering on about the commitment to train forever, only to see him burn hot and turn cold. I wonder if this “dabbler” then runs to the next thing that excites and repeats the process?

The dilettante on the other hand has a self-image to maintain and reinforce. As training challenges and chips away at his being, threatening his self-image, he builds walls in response to the intrusive nature of the truth. Honest training is corrosive to false facades and this person in self-defense needs to find fault with the dojo, the art, the teacher and/or his dojo mate in order to withdraw to his comfort zone. The dilettante falls out of “like” and has to replace the feeling with dislike to keep his carefully scripted self-image intact. If he can’t bend training to his will it becomes inconvenient. As an aside, a teacher can’t teach someone who can’t accept being taught!

I think I have had a little of the dabbler and the dilletante within me. Training intervened and altered my course. My teachers were NOT accommodating. If I wanted to be taught, I accepted unconditionally, their terms for the arrangement.

The student must conform to the training. It is not the other way around as today we often see training conform to the student.

“Keiko” 稽古

Repetitive practice (keiko) replaced the need for excitement and stimulation and protection of my spirit with a more balanced approach to a distant goal. The long journey was accepted with no beginning nor end. Ultimately, I didn’t ask for or expect anything more than a greater depth of understanding and proficiency.

To me, practice, training, and “keiko” were one and the same.

Let me point my finger at Yuri for yet another divergence. Oh, the foil, she has unwittingly become and the revenge I hope to exact! We understand the word “keiko” as practice but in actuality it means a different thing. It means to “think about the old way”. Isn’t that an interesting redirection of the popular use of the concept?

“Sincere Training”, at face value seems easy enough to understand. But how many of us have taken the time to appreciate the definitions we apply to it? We have to balance our lives and can’t be wholly consumed by training. Heck, there’s too many books I’ve left unread!

Training is not a purely physical thing but through training, the mind can be released and freed to wander. Arduous training allows us to “let go”. In a modern world, our minds control our success but budo is experiential. Intellectualization can interfere with progress. Before a harmonious balance can be struck between two seemingly ends of the spectrum between physical and mental activity, we must learn how to learn and how to let go. Keiko is the key with repetitive physical training being the starting point for success. Intellectualization of the process should come later and definitely after learning how to breath.

We all know some contemporary that wants to play-act being a high-ranking Samurai. Let’s not forget, that for most of their existence, the bushi class were ruthless killers where less than 2% of the population exerted absolute control over the population.

Over-romanticized by popular culture and state propaganda, the warrior class was sanitized, and rarely true as more than an ideal. Most of us could never have conformed to the bushi way of life. I for one don’t think I would want to associate with someone that thinks that they could. I’ll save this thread and the concerns about letting anyone train at a home dojo for another day.

I wouldn’t dismiss however, that this fantasy, much like enjoying anime, can be an enticing hook. Acting and role-playing can ignite an interest and its risk free compared to reality.

In budo the training must eventually trigger a personal transformation. Training should be brutally honest and peel away who we wish others to know us as for who we truly are.

Unglamorous repetitive training must forge, probably in a less emotionally satisfying way the foundations of knowing. The challenge is to work thru the hard labor and come to love what you do.

At some point, to avoid delusion, context must be introduced. The collision of cultures might be easy to grasp intellectually. What I write here, you can understand. Breakdowns in communication are attributed to the person offering up the message – not the receiver. But at what point must the receiver truly be receptive and responsible for the message as well? The language of budo must not only be learned but internalized.

Down deep in the marrow, we often miss the greater point, from which our own personal budo journeys are not immune.

For the person who conveniently places themselves at the pinnacle of Japanese society by training in modern day budo, I’d suggest that they probably had no better chance of being a part of that caste than being part of the Billionaire class today. And as a side note, to any student that succeeds in the later should know that your dues will go up – a lot!

The caste system upon which Japanese warrior conduct was predicated was replete with social restrictions. Permeating the day to day activities in ways that were unimaginably oppressive to us. Today, language still reflects the constraints by gender and reinforces a vertical society. Americans can read about it, study it, but can’t really appreciate it unless they get the chance to live it.

Yuri and I have experienced, more often than we can count, the number of times that we were destined to be given the short end of the stick (pardon the pun) in our interactions within this vertical society.

So, the next time you put on your hakama袴, take a moment to appreciate that if anyone but a bushi 武士wore the garment and got found out, the punishment could be death. Understand too, the fear, a farmer might have, working his fields at the sight of someone far off but heading his way wearing a hakama. The social weight of the hakama was very heavy to wear.

I don’t write about this to dampen passion. I desire to ignite and stimulate your interests in pursuit of healthy budo.

To me, part of the challenge of learning, is coming to appreciate as much as possible within historical context. It’s okay to start off with a romantic view of things but eventually, your growth and any real learning experience needs to be “structured” and built on a strong foundation. Hmmmm, could we use the word “kamae” 構え here?

Speaking of “structures”, we now enjoy a new dojo genkan 道場玄関or entryway. I’ve talked about the fact that only warrior homes were allowed to have genkan 玄関, which is why today, every Japanese abode, no matter how modest, has at least the symbol of a genkan where shoes can be removed and mentally, a place to receive guests exists.

Have we also discussed that no one of less that warrior class was allowed to have a two-story home? The idea was that the warrior should never be looked down upon by an inferior being. This hard and fast rule wasn’t without exceptions, especially if you were a rich soy, sake or rice merchant.

Still, we do encounter those that resist giving up the samurai fantasy thing. My advice for those folks is to remind them that a child born into a warrior family, was removed to a stable to be with the other boys around age five or six. They wore their distinctive hair styles “chomagei”, 丁髷 hakama, and wooden swords as they were inculcated into the warrior class.

They studied the Chinese Classics and treatises on the art of war thru rote memorization. Duty, the weight of responsibilities, behavior, and place, might not seem so challenging when read but imagine being constantly told that your every action judged not only you but your family as well. One might never recover “socially” from an infraction made early on. Even today, we can see obvious vestiges of this form of social pressure in schools and business as well as social organizations.

And like warrior castes in other cultures, there was a high rate of molestation. A large fraction of the warrior class would do their duty, get married, have children but saved love for male companions with whom they could better relate.

Today’s “wannabe” starts late and gets to avoid a tremendous portion of the bushi experience. Let’s start with that top knot. The pate wasn’t shaved with a sharp blade. To demonstrate mental toughness, each hair was plucked one at a time.

And we haven’t even learned how to walk yet! Oh, in the dojo, we teach walking for budo and we struggle with it.

Yuri tested me again at lunch today. She asked if in budo it was harder to learn how to walk back and forth or sideways? For me this was an easy question to answer. As hard as it is to move sideways, moving forward and back is much harder.

You can imagine how hard it would be to walk like the bushi of old. The left and right sides of the body move in unison not alternatively. By contrast, we walk, alternating left leg and right arm. I suspect that our “wannabe” friends would fail in attempts to overcome this obstacle. It might be physically difficult. It would definitely be mentally tiresome and socially mocked.

Once we have that warrior gait down, let’s remember that a warrior would NEVER cut corners when walking, almost pivoting when turning right or left. Prepare too, to get wet, as a true warrior NEVER runs in the rain. Think of the money saved on umbrellas.

To me, practice, training, and “keiko” were one and the same.

Let me point my finger at Yuri for yet another divergence. Oh, the foil, she has unwittingly become and the revenge I hope to exact! We understand the word “keiko” as practice but in actuality it means a different thing. It means to “think about the old way”. Isn’t that an interesting redirection of the popular use of the concept?

“Sincere Training”, at face value seems easy enough to understand. But how many of us have taken the time to appreciate the definitions we apply to it? We have to balance our lives and can’t be wholly consumed by training. Heck, there’s too many books I’ve left unread!

Training is not a purely physical thing but through training, the mind can be released and freed to wander. Arduous training allows us to “let go”. In a modern world, our minds control our success but budo is experiential. Intellectualization can interfere with progress. Before a harmonious balance can be struck between two seemingly ends of the spectrum between physical and mental activity, we must learn how to learn and how to let go. Keiko is the key with repetitive physical training being the starting point for success. Intellectualization of the process should come later and definitely after learning how to breath.

We all know some contemporary that wants to play-act being a high-ranking Samurai. Let’s not forget, that for most of their existence, the bushi class were ruthless killers where less than 2% of the population exerted absolute control over the population.

Over-romanticized by popular culture and state propaganda, the warrior class was sanitized, and rarely true as more than an ideal. Most of us could never have conformed to the bushi way of life. I for one don’t think I would want to associate with someone that thinks that they could. I’ll save this thread and the concerns about letting anyone train at a home dojo for another day.

I wouldn’t dismiss however, that this fantasy, much like enjoying anime, can be an enticing hook. Acting and role-playing can ignite an interest and its risk free compared to reality.

In budo the training must eventually trigger a personal transformation. Training should be brutally honest and peel away who we wish others to know us as for who we truly are.

Unglamorous repetitive training must forge, probably in a less emotionally satisfying way the foundations of knowing. The challenge is to work thru the hard labor and come to love what you do.

At some point, to avoid delusion, context must be introduced. The collision of cultures might be easy to grasp intellectually. What I write here, you can understand. Breakdowns in communication are attributed to the person offering up the message – not the receiver. But at what point must the receiver truly be receptive and responsible for the message as well? The language of budo must not only be learned but internalized.

Down deep in the marrow, we often miss the greater point, from which our own personal budo journeys are not immune.

For the person who conveniently places themselves at the pinnacle of Japanese society by training in modern day budo, I’d suggest that they probably had no better chance of being a part of that caste than being part of the Billionaire class today. And as a side note, to any student that succeeds in the later should know that your dues will go up – a lot!

The caste system upon which Japanese warrior conduct was predicated was replete with social restrictions. Permeating the day to day activities in ways that were unimaginably oppressive to us. Today, language still reflects the constraints by gender and reinforces a vertical society. Americans can read about it, study it, but can’t really appreciate it unless they get the chance to live it.

Yuri and I have experienced, more often than we can count, the number of times that we were destined to be given the short end of the stick (pardon the pun) in our interactions within this vertical society.

So, the next time you put on your hakama袴, take a moment to appreciate that if anyone but a bushi 武士wore the garment and got found out, the punishment could be death. Understand too, the fear, a farmer might have, working his fields at the sight of someone far off but heading his way wearing a hakama. The social weight of the hakama was very heavy to wear.

I don’t write about this to dampen passion. I desire to ignite and stimulate your interests in pursuit of healthy budo.

To me, part of the challenge of learning, is coming to appreciate as much as possible within historical context. It’s okay to start off with a romantic view of things but eventually, your growth and any real learning experience needs to be “structured” and built on a strong foundation. Hmmmm, could we use the word “kamae” 構え here?

Speaking of “structures”, we now enjoy a new dojo genkan 道場玄関or entryway. I’ve talked about the fact that only warrior homes were allowed to have genkan 玄関, which is why today, every Japanese abode, no matter how modest, has at least the symbol of a genkan where shoes can be removed and mentally, a place to receive guests exists.

Have we also discussed that no one of less that warrior class was allowed to have a two-story home? The idea was that the warrior should never be looked down upon by an inferior being. This hard and fast rule wasn’t without exceptions, especially if you were a rich soy, sake or rice merchant.

Still, we do encounter those that resist giving up the samurai fantasy thing. My advice for those folks is to remind them that a child born into a warrior family, was removed to a stable to be with the other boys around age five or six. They wore their distinctive hair styles “chomagei”, 丁髷 hakama, and wooden swords as they were inculcated into the warrior class.

They studied the Chinese Classics and treatises on the art of war thru rote memorization. Duty, the weight of responsibilities, behavior, and place, might not seem so challenging when read but imagine being constantly told that your every action judged not only you but your family as well. One might never recover “socially” from an infraction made early on. Even today, we can see obvious vestiges of this form of social pressure in schools and business as well as social organizations.

And like warrior castes in other cultures, there was a high rate of molestation. A large fraction of the warrior class would do their duty, get married, have children but saved love for male companions with whom they could better relate.

Today’s “wannabe” starts late and gets to avoid a tremendous portion of the bushi experience. Let’s start with that top knot. The pate wasn’t shaved with a sharp blade. To demonstrate mental toughness, each hair was plucked one at a time.

And we haven’t even learned how to walk yet! Oh, in the dojo, we teach walking for budo and we struggle with it.

Yuri tested me again at lunch today. She asked if in budo it was harder to learn how to walk back and forth or sideways? For me this was an easy question to answer. As hard as it is to move sideways, moving forward and back is much harder.

You can imagine how hard it would be to walk like the bushi of old. The left and right sides of the body move in unison not alternatively. By contrast, we walk, alternating left leg and right arm. I suspect that our “wannabe” friends would fail in attempts to overcome this obstacle. It might be physically difficult. It would definitely be mentally tiresome and socially mocked.

Once we have that warrior gait down, let’s remember that a warrior would NEVER cut corners when walking, almost pivoting when turning right or left. Prepare too, to get wet, as a true warrior NEVER runs in the rain. Think of the money saved on umbrellas.

Being “Unsenseisorial”

At the Rembukan, I was often accused of being “unsenseisorial”. Don’t look the word up as I made it up! I think I was also the very first one to coin words like “Mcbudo” and “Mcjodo” but it’s’ in the popular lexicon today!

A “sensei” is supposed to have a certain demeanor. I wholly concur, at least in theory. There is a certain dimension that I think is lost when someone puts on false airs until the great transformation takes place and one moves to that lofty space.

I certainly wanted the dojo environment to be appropriate. But the tone changes based upon circumstances too. I use humor. I believe that regardless of your state of mind, that you should remain vigilant and practice zanshin 残心 as best you can. Can you laugh and keep your concentration as well? In keiko, sometimes we get stuck and humor can free us of the mental traps we find ourselves in. In budo, there is also a time for coercion. Training is a serious thing. In short there is a balance to be had and many tools available to achieve ultimate success. We have to strive to strike a balance between maintaining our traditional and uncompromised approach to training with the realities that we don’t live in 19th century Japan.

In a way, we are the watchmen of the arts we study. Regardless of our best efforts, key lessons both evolve and devolve over time. We’re not rigorously testing our theories in duels to the death. We’re not able to wholly disseminate the foundations of these ryu-ha to our students because we haven’t grasped let alone perfected everything there is to know. The quality of teachers has changed. So has the quality of the students. And then there is the issue of the amount of time we’re willing to invest in training. I encourage all of you to surpass me in skills. I won’t “give” it to you – you’ll have to earn it. I want you to strive for and achieve as much as you can.

Sadly, in my experience, I haven’t found that all teachers embrace this idea. If a really great technician and “sensei” 先生refuses to pass on as much as possible, is proper service given to the art? Is this the “senseisorial” way of behaving towards a student?

Yuri shared with me a quote out of 4th century BCE. China. “The dye is richer than the leaf” or “Ai yori auku” 藍より青く or “Syuturan no Homare” 出藍の誉れ

In essence, a good teacher is compared to an indigo plant – the same plant used to dye your uwagi. The idea is that the plant’s leaf color pales in comparison to the rich dye it produces. The indigo dye become brighter with each successive generation. There should be an emphasis on continued learning and advancing knowledge.

I love allegories, and deeper thought reveals something about continuity, not just in the transmission of the thing but in the relationship between teacher and student. Without the teacher, the student wouldn’t exist. As the teacher inevitably fades, the thing worth disseminating becomes more important. Also, each plant is unique and the dye from many plants must be blended together to get consistent color. It is the nuanced differences that are the more valuable when the leaves are sorted.

It should be acknowledged, that Japanese students do not easily cut relationships, but they are allowed to fade. When someone departs the dojo, de-emphasizing the relationship doesn’t mean that the knowledge and energy imparted can be extracted, erased, or ignored. There is an obligation that can never be repaid.

Here outside Japan, one of my greatest disappointments is the fact that my students can hear about this but just can’t grasp it. Of all of the departures over the years, I can count on one hand the number of students that have done the right thing. It’s sad and those ghosts are not treated kindly at our table.

A “sensei” is supposed to have a certain demeanor. I wholly concur, at least in theory. There is a certain dimension that I think is lost when someone puts on false airs until the great transformation takes place and one moves to that lofty space.

I certainly wanted the dojo environment to be appropriate. But the tone changes based upon circumstances too. I use humor. I believe that regardless of your state of mind, that you should remain vigilant and practice zanshin 残心 as best you can. Can you laugh and keep your concentration as well? In keiko, sometimes we get stuck and humor can free us of the mental traps we find ourselves in. In budo, there is also a time for coercion. Training is a serious thing. In short there is a balance to be had and many tools available to achieve ultimate success. We have to strive to strike a balance between maintaining our traditional and uncompromised approach to training with the realities that we don’t live in 19th century Japan.

In a way, we are the watchmen of the arts we study. Regardless of our best efforts, key lessons both evolve and devolve over time. We’re not rigorously testing our theories in duels to the death. We’re not able to wholly disseminate the foundations of these ryu-ha to our students because we haven’t grasped let alone perfected everything there is to know. The quality of teachers has changed. So has the quality of the students. And then there is the issue of the amount of time we’re willing to invest in training. I encourage all of you to surpass me in skills. I won’t “give” it to you – you’ll have to earn it. I want you to strive for and achieve as much as you can.

Sadly, in my experience, I haven’t found that all teachers embrace this idea. If a really great technician and “sensei” 先生refuses to pass on as much as possible, is proper service given to the art? Is this the “senseisorial” way of behaving towards a student?

Yuri shared with me a quote out of 4th century BCE. China. “The dye is richer than the leaf” or “Ai yori auku” 藍より青く or “Syuturan no Homare” 出藍の誉れ

In essence, a good teacher is compared to an indigo plant – the same plant used to dye your uwagi. The idea is that the plant’s leaf color pales in comparison to the rich dye it produces. The indigo dye become brighter with each successive generation. There should be an emphasis on continued learning and advancing knowledge.

I love allegories, and deeper thought reveals something about continuity, not just in the transmission of the thing but in the relationship between teacher and student. Without the teacher, the student wouldn’t exist. As the teacher inevitably fades, the thing worth disseminating becomes more important. Also, each plant is unique and the dye from many plants must be blended together to get consistent color. It is the nuanced differences that are the more valuable when the leaves are sorted.

It should be acknowledged, that Japanese students do not easily cut relationships, but they are allowed to fade. When someone departs the dojo, de-emphasizing the relationship doesn’t mean that the knowledge and energy imparted can be extracted, erased, or ignored. There is an obligation that can never be repaid.

Here outside Japan, one of my greatest disappointments is the fact that my students can hear about this but just can’t grasp it. Of all of the departures over the years, I can count on one hand the number of students that have done the right thing. It’s sad and those ghosts are not treated kindly at our table.

Tenuki, Nukiuchi, and Te no uchi…

“Tenuki” 手抜き is a term for cutting corners, for taking short cuts. It connotes something negative.

The “nuki” 抜く in nukiuchi 抜き打ち uses the same ideogram. The meaning of nuki, 抜き in this instance, expresses the feeling of drawing, expanding or spreading out.

In swordsmanship, this is often expressed in translation by Japanese as drawing and/or cutting big. I like the mental imagery of expanding and spreading out better.

I don’t practice drawing and then cutting. But there’s “maai” 間あい between the nukiuchi 抜き打ち /sayabiki 鞘引き and the sayabanari 鞘離れ and in that instant the distance and target are locked into the final movement. This concept is hard to convey and critical to successful iai in particular. We see/feel a well performed nukiuchi. 抜き打ち We can feel that expansion and pressure – the threat. We can act on the results with our opponent.

Let’s take a moment to consider that a Japanese student hearing “nukiuchi” has a much deeper appreciation for the message being conveyed as the feeling of “expanding” is not the same as “cutting big” is to us.

“Te no uchi” 手の内 in budo is often treated the same as mentioning Lord Voldemort of Harry Potter fame. The “te” 手 or hand is the same as “te-nuki” 手抜き. The meanings are not quite opposite in nature. There is a concept that the thing to be known is hidden from view inside the hand.

In Iai, it is interpreted with a more literal sense of instructing a student how things work but only when the teacher will dare mention Voldemort out loud. Because truly, otherwise the path to discovery is hidden and might never be revealed and all the sincere training in the world might not discover the lessons.

Like “kamae” 構え, te no uchi 手の内 is in common, non-budo specific use. We might understand the concept as “keeping your cards close to your chest”.

Perhaps you noticed that I slipped “sayabiki” and “sayabanare” into my writings…

Yuri and I took another excursion today and it reminded me of a story I’d like to share. Oh, yes, I’m not ready to write more about sayabiki/sayabanare yet. Please persevere.

Kaminoda Sensei and entourage visited our dojo for many years. He always remarked on how much he loved our dojo floor which is unfinished pine. Unlike most Japanese training spaces today, there is no varnish. He would often say that our unfinished floor was very healthy for the feet.

Speed forward, one of Yuri’s childhood friends is, with her husband, a visiting scholar at Oxford, finishing up a two-year stint. She is expecting a grandchild soon. As English textiles are very good, she wanted to procure some outfits as grandmothers do. In picking out clothing, she was stymied by the fact that she could not find infant sleepwear that didn’t have the feet covered.

There’s no budo story here but the Japanese believe that the baby’s feet should be left bare because the feet breath. This was the basis for Kaminoda Sensei’s firm belief that the naked foot on an unvarnished floor is not only a good thing for training but for health. This concept is widely held amongst budo teachers.

Like many of the ideas I’m expressing, they’re not necessarily sins of omission when no one alerts us to what is so mundane to them as to be taken for granted.

As I opined earlier, more and more, we see how the most basic things within everyday Japanese culture, are a natural subtext to our budo training too. Those, who wear tabi足袋 or Kung Fu slippers all the time, might be missing out on important lessons. It would be hard to fully appreciate that “te no uchi” is utilized by the feet. It controls dynamic movement and having a solid base. Here too, in Japan no one would ever want to put the dirty “feet” in the same sentence as something as revered as “te no uchi”.

Coming soon…

The “nuki” 抜く in nukiuchi 抜き打ち uses the same ideogram. The meaning of nuki, 抜き in this instance, expresses the feeling of drawing, expanding or spreading out.

In swordsmanship, this is often expressed in translation by Japanese as drawing and/or cutting big. I like the mental imagery of expanding and spreading out better.

I don’t practice drawing and then cutting. But there’s “maai” 間あい between the nukiuchi 抜き打ち /sayabiki 鞘引き and the sayabanari 鞘離れ and in that instant the distance and target are locked into the final movement. This concept is hard to convey and critical to successful iai in particular. We see/feel a well performed nukiuchi. 抜き打ち We can feel that expansion and pressure – the threat. We can act on the results with our opponent.

Let’s take a moment to consider that a Japanese student hearing “nukiuchi” has a much deeper appreciation for the message being conveyed as the feeling of “expanding” is not the same as “cutting big” is to us.

“Te no uchi” 手の内 in budo is often treated the same as mentioning Lord Voldemort of Harry Potter fame. The “te” 手 or hand is the same as “te-nuki” 手抜き. The meanings are not quite opposite in nature. There is a concept that the thing to be known is hidden from view inside the hand.

In Iai, it is interpreted with a more literal sense of instructing a student how things work but only when the teacher will dare mention Voldemort out loud. Because truly, otherwise the path to discovery is hidden and might never be revealed and all the sincere training in the world might not discover the lessons.

Like “kamae” 構え, te no uchi 手の内 is in common, non-budo specific use. We might understand the concept as “keeping your cards close to your chest”.

Perhaps you noticed that I slipped “sayabiki” and “sayabanare” into my writings…

Yuri and I took another excursion today and it reminded me of a story I’d like to share. Oh, yes, I’m not ready to write more about sayabiki/sayabanare yet. Please persevere.

Kaminoda Sensei and entourage visited our dojo for many years. He always remarked on how much he loved our dojo floor which is unfinished pine. Unlike most Japanese training spaces today, there is no varnish. He would often say that our unfinished floor was very healthy for the feet.

Speed forward, one of Yuri’s childhood friends is, with her husband, a visiting scholar at Oxford, finishing up a two-year stint. She is expecting a grandchild soon. As English textiles are very good, she wanted to procure some outfits as grandmothers do. In picking out clothing, she was stymied by the fact that she could not find infant sleepwear that didn’t have the feet covered.

There’s no budo story here but the Japanese believe that the baby’s feet should be left bare because the feet breath. This was the basis for Kaminoda Sensei’s firm belief that the naked foot on an unvarnished floor is not only a good thing for training but for health. This concept is widely held amongst budo teachers.

Like many of the ideas I’m expressing, they’re not necessarily sins of omission when no one alerts us to what is so mundane to them as to be taken for granted.

As I opined earlier, more and more, we see how the most basic things within everyday Japanese culture, are a natural subtext to our budo training too. Those, who wear tabi足袋 or Kung Fu slippers all the time, might be missing out on important lessons. It would be hard to fully appreciate that “te no uchi” is utilized by the feet. It controls dynamic movement and having a solid base. Here too, in Japan no one would ever want to put the dirty “feet” in the same sentence as something as revered as “te no uchi”.

Coming soon…